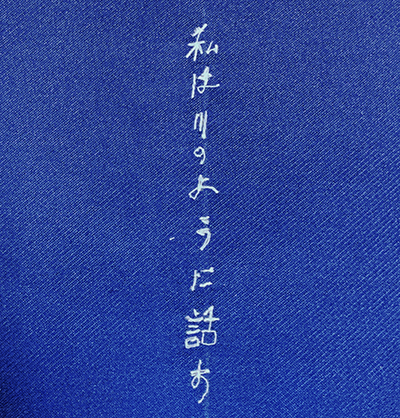

丹山河從八仙嶺腳下開始流淌,匯集山泉及雨水,一路蜿蜒西行,流匯成梧桐河之後向北延伸,依次與麻笏河、石上河與雙魚河匯流,最終在羅湖融匯為深圳河。「九龍界限街以北,深圳河以南」,正是1898年中英簽署的《展拓香港界址專條》中租借給英國的新界地區界址。彼時,英國派遣至新界的印度籍地理測量師為這裡河流標註名稱,或許是出於鄉愁,縱貫北區的梧桐河被他們以「印度河」命名,而印度河數條重要的支流則成為梧桐河支流的名稱:傑赫勒姆河(丹山河)、比亞斯河(雙魚河)、薩特萊傑河(石上河)。接受精確定位與繪圖訓練的測量師們不乏傷感地為他鄉的河流冠以故鄉的名字,藉助命名在殖民版圖中連接起充滿溫柔與感傷的情感紐帶。然而,現代測繪學的視野卻只限於對領土的標註、對界線的劃分,它看不見河水下的情感潛流,聽不見河床上砂石低語的故事。於是,以「印度河」為起點,羅玉梅開始她對新界北部河流的「測繪」。她的測量所關心的,是天空到水底的距離,季節到季節的長度,記憶與願望的形狀。 (河上沒有人唱歌展覽圖錄,So Much Water 節選,瞿暢撰)

Tan Shan River begins at the foot of Pat Sin Leng, gathering mountain springs and rainwater as it meanders westward, joins Ng Tung River and extending northward, followed by Ma Wat River, Shek Sheung River and Sheung Yue River, before finally becoming Sham Chun River in Lo Wu. ‘North of Boundary Street on the Kowloon Peninsula and south of the Sham Chun River’, later known as the New Territories, were leased to the United Kingdom under the Convention for the Extension of Hong Kong Territory signed between Qing China and the United Kingdom in 1898. At that time, Indian surveyors sent by the British to the New Territories named the rivers. Perhaps out of a yearning for home, they named Ng Tung River that ran through the northern district the ‘Indus’, and the tributaries of Ng Tung River were named after the other important tributaries of the Indus River: Jhelum (Tan Shan River), Beas (Sheung Yue River), Sutlej (Shek Sheung River). Trained to be precise in positioning and mapping, the surveyors, in a sentimental gesture, conferred names from home upon the rivers in a foreign land, and through the act of naming, connected the emotional bonds of utmost tenderness and melancholy across the colonial map. Yet modern surveying and cartography is limited to the marking of territories and drawing of boundaries; it does not discern the emotional undercurrents under the water, does not hear the murmured stories of the sands and debris on the river bed. And so, beginning with ‘Indus River’, Law Yuk Mui ‘surveys and maps’ her own rivers in the northern New Territories. She is solely interested in the distance between the sky and the river bed, the length between seasons, the shapes of memories and prayers. (excerpt from “So Much Water” by Qu Chang, There Is No One Singing On The River’s exhibition catalogue)

(please click page 2 to continue reading)